Robert Duvall, acting legend known for intense roles, dead at 95

Published in Entertainment News

When Robert Duvall was floundering around in college, his father, a career Navy man who retired with the rank of rear admiral, told him to shape up — and start acting.

“I wasn’t pushed into it but suggested into it,” Duvall once told an interviewer. “They figured I did skits around the house. They figured I had a calling, or whatever, in that line.”

They figured correctly. With his weathered face and receding hairline, he did not stand out for his movie star looks but for the intensity and depth he brought to his craft. New York Times film critic Vincent Canby in 1980 called him “the best we have, the American Olivier.”

Duvall, a veteran of many leading roles but best known for his sharp portrayal of supporting characters like the Godfather’s Irish-American consigliere and the unhinged Army colonel who loved the smell of napalm in the morning, died at 95, his wife Luciana Duvall announced on Facebook.

“Bob passed away peacefully at home, surrounded by love and comfort,” she wrote.

While he could play comic characters like Maj. Frank Burns, the priggish Army doctor who was obsessed with nurse Hot Lips Houlihan in “M*A*S*H,” Duvall specialized in tightly wound tough guys.

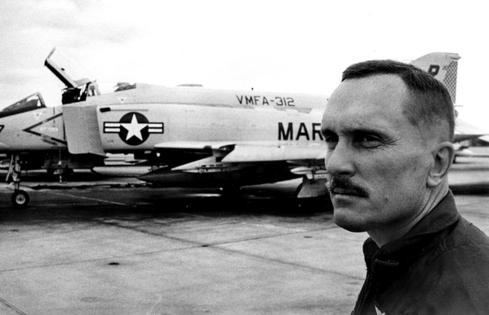

In “The Great Santini,” he was a Marine fighter pilot who was as overbearing and explosive with his family as with the men under his command. In “The Apostle,” he was a preacher who killed his wife’s lover with a baseball bat. In “The Godfather” and “The Godfather Part II,” he was Tom Hagen, a buttoned-down attorney who was loyal to his mob bosses and lethal to those who got in their way. He was an expert, one critic said, in playing “self-controlled men who should not be pushed too far.”

Duvall was known for pouring himself into his characters. He could move with the grace of the tango aficionado he became or with the slow, pained gait of the cancer-ridden editor he played in “The Paper.” He was a keen student of dialect; doing movies in the South, he meandered down backroads, learning just the right way to frame a question in rural Mississippi or deliver a compliment in west Texas.

He loved playing country people and particularly loved Westerns.

“That’s our genre,” he said in a 2011 interview with the News and Advance in Lynchburg, Va., near his home on a 362-acre horse farm. “The English have Shakespeare, the French Moliere, and the Russians Chekhov. The Western is ours.”

When asked about his acting technique, Duvall would describe it as simply as his favorite character — Augustus McCrae, the wry trail boss on the TV miniseries “Lonesome Dove” — might have described riding a horse.

“It’s just talking and listening,” Duvall told The Times in 2006. “Nothing’s precious. Just let it sit there and find its own way.”

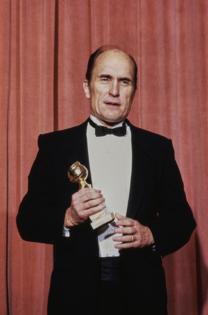

Nominated six times for an Academy Award, Duvall won best actor honors in 1983 for his role as Mac Sledge, a broken-down country singer in the film “Tender Mercies.” A guitar player since childhood, he did his own singing and wrote two of the songs.

Turning down his studio’s offer of a cast party at glitzy Studio 54, Duvall hosted a heartfelt hoedown in his New York City apartment. The crowd ate downhome food cooked by character actor Wilford Brimley, who had flown in from Tennessee. As the party ended at 3 a.m., an exuberant Duvall had everyone join hands for a chorus of “Amazing Grace.”

Willie Nelson — who sang duets with Duvall at the party — told Village Voice columnist Arthur Bell that “Tender Mercies” was dead-on accurate.

“These people Bobby portrayed in his movie, I grew up in those parts and know each of them personally,” he said. “And I’ll probably be that character he plays someday if I don’t take care of myself.”

Many of Duvall’s characters had hardscrabble backgrounds, but Duvall grew up in privilege. Born in San Diego on Jan. 5, 1931, he was raised in places around the U.S. where his naval officer father was posted.

When he was 10, the future star of so many Westerns rode his first horse and got to know his first Texans, on a family trip to see his mother’s relatives.

By his teen years in Annapolis, Maryland, Duvall had become an excellent mimic, absorbing dialects and mannerisms wherever he happened to be. He did hilarious impressions of people like his cousin Fagin Springer, a singing evangelist from Virginia, and the tough old cowhands on his uncle’s Montana ranch. Years later, on the set of “The Godfather,” he did impressions of Marlon Brando.

In his more than 85 movies, many of his characters were heavy drinkers, but not Duvall. He went to a Christian Science boarding school in St. Louis and to Principia College, a Christian Science college in Elsah, Illinois, and never smoked or drank.

When the affable, athletic Duvall was nearly kicked out of college for poor grades, administrators summoned his parents for an emergency meeting. Everyone agreed he was miscast as a history major. The boy’s only talent, besides tennis, appeared to be acting.

Switching to drama — a decision supported by his parents, who wanted him to stay in school — he turned his academic career around.

In a college production of Arthur Miller’s “All My Sons,” Duvall so deeply merged into the character of a ruthless businessman haunted by a bad decision that he found himself crying. “That clinched it,” wrote Judith Slawson in “Robert Duvall: Hollywood Maverick,” a 1985 biography. “Acting was for him.”

Graduating in 1953, Duvall was drafted into the Army. He trained in radio repair at Camp Gordon in Georgia but spent his off-duty time with a community theater group in nearby Augusta. When he left the service in 1955, he studied at New York’s Neighborhood Playhouse School of the Theatre, a training ground for such top talents as Gregory Peck, Steve McQueen and Jon Voight.

Sanford Meisner, the school’s legendarily demanding director, was impressed.

“There are only two actors in America,” he told playwright David Mamet years later. “One is Brando, who’s done his best work, and the other is Robert Duvall.”

In New York, Duvall worked night shifts at the post office, washed dishes and kept auditioning. He shared an apartment at Broadway and West 107th Street with a fledgling actor named Dustin Hoffman. The two also palled around with Gene Hackman and James Caan.

Over coffee at Cromwell’s Drugstore, the yet-to-be-discovered actors would discuss the mumbling, moving technique of another young actor.

“If we mentioned Brando once we mentioned him 25 times,” Duvall told The Times in 2014.

After several years of off-Broadway productions, summer stock, and roles in TV dramas like “Naked City” and the “Twilight Zone,” Duvall landed his first Hollywood role in 1962.

As Boo Radley, a mysterious recluse in “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Duvall was on screen for less than five minutes at the film’s end and had no lines. But he played a pivotal character and the film launched a cinematic career that lasted more than five decades.

In the 1979 Vietnam epic “Apocalypse Now,” he delivered one of the most famous lines in the history of film. As the swaggering Lt. Col. Bill Kilgore, he orders U.S. helicopters to destroy a coastal Viet Cong-held village so he and his men could surf there.

“You smell that? Do you smell that? Napalm, son. Nothing else in the world smells like that,” Kilgore says nonchalantly as the village before him erupts in flame. “I love the smell of napalm in the morning.”

Kilgore’s chilling monologue topped the list of best movie speeches in a 2004 BBC poll. Duvall later said he had no idea people would remember it.

Duvall seldom played leading men, but Mac Sledge, in “Tender Mercies,” was a notable breakthrough.

“This is the only film where I’ve heard people say I’m sexy,” he told an interviewer. “It’s real romantic — rural romantic. I love that part almost more than anything.”

Duvall was married three times before meeting Luciana Pedraza, a young woman who was dared by her friends to approach him on a Buenos Aires street and invite him to a tango gathering. She played opposite him in “Assassination Tango,” a 2002 film in which he portrays a hitman dispatched to Argentina. They married in 2005 and for years practiced tango on a dance floor they installed in one of their barns.

In addition to his wife, Duvall is survived by his older brother William, an actor and music teacher. His young brother John died in 2000.

Duvall’s legacy includes a wide range of films, from “True Grit” to “True Confessions.” He played a retired Cuban barber in “Wrestling Ernest Hemingway”; a cynical TV executive in “Network”; a dirt-poor Mississippi farmer in “Tomorrow”; a quietly effective corporate attorney in “A Civil Action”; a middle-aged astronaut in “Deep Impact”; a grizzled cattleman in “Open Range”; a tobacco company bigwig in the satirical “Thank You for Smoking”; and in the miniseries “Ike,” he was Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower.

He also tackled some less commercial projects. In 1977, he directed a documentary about a Nebraska rodeo family, “We’re Not the Jet Set.” In 1983, he wrote and directed “Angelo, My Love,” a drama inspired by and starring gypsies Duvall came to know in New York City

He worked well into his later years. In the 2009 film “Get Low,” he was a backwoods hermit who staged his own funeral. Two years later, he was a rancher and ex-golf pro who takes a young golfer under his wing in the spiritual drama “Seven Days in Utopia.” And four years after that he played an alcoholic and abusive justice in “The Judge,” earning a best supporting actor Oscar nomination — the oldest actor at the time to do so.

In “A Night in Old Mexico” (2014), he played an ill-tempered rancher preparing for suicide after losing his land to foreclosure. His plans change when he meets an adult grandson he never knew he had and the two wander across the border into bars and bordellos and reflect on life.

“No one plays wise old coots more convincingly,” the New York Times said.

Duvall drew on his inner curmudgeon throughout his career.

As an actor who prided himself on an up-close, deep-down knowledge of his characters, he sometimes bristled at direction.

“If I have instincts I feel are right, I don’t want anyone to tamper with them,” he told After Dark magazine in 1973. “I don’t like tamperers and I don’t like hoverers.”

Horton Foote, who adapted “Mockingbird” for the movies and wrote “Tender Mercies,” became one of Duvall’s few lifelong friends in the industry.

When Duvall was checking out Southern churches as he researched “The Apostle,” which he wrote, directed and starred in, the two were frequently in touch on the phone.

“I could always tell he’d been with a different preacher,” Foote told The Times in 2006, “because he’d try out these different voices.”

Authenticity was so important to Duvall that he gave some key roles in “The Apostle” to local people with little or no acting experience.

Rick Dial, who played a small-town radio reporter in the film, was actually a local furniture salesman.

“Rick improvised a lot of his dialogue,” Duvall told Backstage magazine in 2001. “At the end of ‘The Apostle’ when they cart me off, his skin turned a certain color of grief. I don’t know who told him to do that. He just did it.”

For Duvall, known as an actor who “just did it” in film after film, that was the highest kind of praise.

____

Steve Chawkins is a former Times staff writer.

____

©2026 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments