Commentary: What can we do as the Trump administration sanitizes civics education?

Published in Op Eds

On Constitution Day, the Department of Education announced the America 250 Civics Education Coalition, partnering with organizations such as Turning Point USA and Hillsdale College to shape civics curriculum nationwide. The timing is no coincidence: As America approaches the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, we face a fundamental choice about how we understand our democratic heritage and our democratic future.

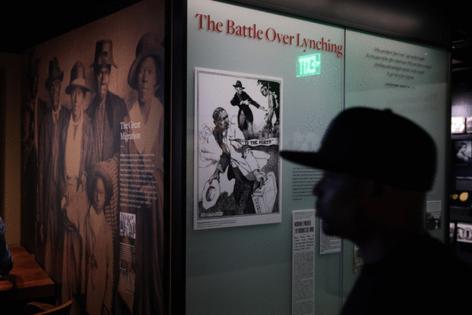

The coalition’s formation comes amid broader efforts to sanitize American education. Laws restricting how educators can discuss slavery, segregation and ongoing injustices are spreading across states. Executive orders demanding the erasure of historical truths alongside directives to cleanse museums and national parks of the stories of Black and Indigenous people are resulting in swift erasure of minoritized histories. Books centering the experiences of communities of color, LGBTQ+ individuals and other marginalized groups are being challenged and removed. Educators from K-12 and universities face disciplinary action for social media posts that challenge conservative narratives or highlight instances of racism.

Now the organizations driving these restrictions are positioned to shape how America’s young people learn about citizenship and democracy itself. But when civics education erases the experiences of marginalized communities and teachers face punishment for discussing historical realities, we lose the thinking skills that make democratic participation possible. This contradicts the very ideals embedded in our founding documents — that governments derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed” and require an informed citizenry capable of meaningful consent and holding power accountable. The Declaration of Independence further recognized that when faced with “a long train of abuses and usurpations” designed to establish despotism, “it is their right, it is their duty” for people to alter their government.

But when students learn sanitized versions of history that erase struggle and complexity, they develop unrealistic expectations about how democratic progress happens. They miss the vital lesson that democracy requires active participation, difficult conversations and ongoing vigilance to protect and expand rights for all people. Most critically, citizens can only fulfill their constitutional duty to recognize and resist government overreach when they possess the civic knowledge and critical thinking skills to identify such patterns, the very capacities now under systematic attack.

Since formal institutions are failing their constitutional responsibility to maintain an informed citizenry — many not by choice, but because they’re being systematically constrained and defunded— communities must act. We must rebuild the intellectual foundations of democratic participation in our own communities — teaching people to think critically about information, evaluate digital sources and online manipulation, seek out multiple perspectives, engage directly with primary sources and participate meaningfully in local civic life.

Consider what this looks like in practice. Instead of accepting simplified narratives about historical events, people learn to read original documents — slave narratives alongside founding texts, Supreme Court decisions alongside civil rights speeches, executive orders alongside congressional testimony challenging them. Rather than consuming information passively, people develop the habit of asking who created particular sources, what agendas might be at work and whose voices are missing from the conversation.

This approach recognizes that democratic citizenship requires intellectual courage: the willingness to encounter perspectives that challenge our assumptions and grapple with evidence that complicates simple stories. When people understand that historical events look different from different vantage points, they develop the cognitive flexibility essential for democratic discourse.

The responsibility falls to all of us. Libraries can create programming that introduces people to primary historical sources. Community organizations can host discussions modeling respectful engagement with difficult topics. Universities can open their doors wider, offering public lectures, community partnerships and adult education programs that bring rigorous scholarship to broader audiences. Parents and educators can demonstrate intellectual curiosity, showing young people that questions matter more than easy answers. Local groups can organize civic education efforts that teach practical skills while building habits of critical thinking.

None of this requires permission from state legislatures or school boards. But let’s be clear: This work is hard. It takes time, resources and uncomfortable conversations that many would rather avoid. Even so, communities can build these intellectual capacities regardless of what happens in formal educational institutions. Communities can also learn from each other, sharing strategies and resources across networks of democratic educators. In doing so, we fulfill the founders’ vision of an informed citizenry while expanding it to include all the voices they overlooked.

When formal systems fail to provide comprehensive civic education, communities must fill the gap. When official narratives become sanitized, we must seek fuller truths. When critical thinking is openly attacked in schools, we must cultivate it everywhere else.

The stakes could not be higher. Democracy’s survival depends on citizens who can think clearly, engage respectfully with difference and act courageously. That work begins wherever we are, with whoever will join us.

____

Stephanie R. Toliver is an assistant professor of curriculum and instruction at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and a public voices fellow with The OpEd Project.

___

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments