Commentary: The wrong way to fight homelessness

Published in Op Eds

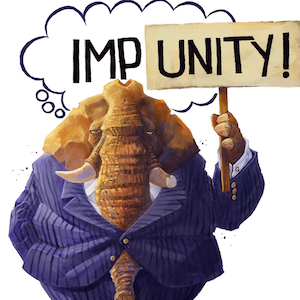

Across the country, cities have taken to cracking down on people who lack housing — not by finding them places to live, but by kicking them out of the places they are seeking shelter. These mass encampment evictions owe in part to a 2024 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, that allowed cities to enforce bans on public camping even if shelters in the area are full.

That decision drew immediate condemnation from Carrie Ann Shirota, policy director at ACLU of Hawaii, who said in a press release, “The U.S. Supreme Court’s terrible ruling continues in the shameful tradition of choosing to remove unhoused people from public view rather than provide our community members with the resources they actually need: affordable housing and support services.”

Following the court’s ruling, there have been increased sweeps of encampments, forcing people to move from tents, camper vans or other makeshift shelters. One hundred fifty municipalities, including a number of small cities in California and the Pacific Northwest, have since passed outdoor camping bans, paving the way for cities to conduct sweeps. In 2024, city records in Portland, Oregon, noted that more than 20 encampments were dismantled per day.

When these “clean-ups” occur, encampment occupants often have little to no notice to take what possessions they can before the city sends in waste management teams to bulldoze and trash any remaining items. Those who cannot do so may lose everything they own, including important documents such as birth certificates and identification, medications and items of sentimental value. The trauma, material setbacks, and disconnection from social services that result from these sweeps may increase displaced people’s risk of overdose and death.

One recent sweep in San Jose felt particularly cruel. Despite public attempts to dissuade the city, a camp in Columbus Park was cleared in June, including the razing of a well-tended garden maintained by unhoused resident Nancy Lopez. “Oh, I want to cry,” Lopez told a local news outlet that day. “Because that’s a lot of hard work. It’s a lot of hard work.”

For unhoused people, being allowed to exist in public is essential for accessing basic needs such as public transport, health care, education and commerce. Instead of improving their quality of life, vagrancy and anti-camping laws force them into the shadows, where they must struggle to survive.

What’s more, the immediate emergency of having to find a new place to shelter after a sweep can be detrimental for unhoused people’s health outcomes. On average, unhoused people die 20 years earlier than their housed counterparts. Research also suggests that unhoused people in their fifties are at increased risk for developing functional, cognitive and visual impairment associated with old age.

Moving people on from encampments doesn’t solve any problems beyond hiding their need for housing from those who would prefer to look away. Yes, some people may move into temporary or transitional housing as a result of an encampment sweep, but others cannot or will not — in many cases, living on the streets and in encampments is safer and more accessible than the shelter system, which can be fraught with restrictive rules, violence, excessive noise and disease.

Without affordable housing options, those left behind will simply have to find somewhere else to put a bed down.

As Jillian Olmsted, executive director of The INN Between in Salt Lake City, a medical respite unit and hospice for unhoused people, explains in an interview, “These sweeps don’t just take away belongings — they can endanger lives, rip away sources of companionship and deepen the trauma people already carry.” Each disruption creates further barriers to finding more sustainable housing options.

The National Health Care for the Homeless Council suggests that the cities currently sweeping encampments should instead focus their efforts on connecting people to permanent housing, health care and much-needed support services. What’s needed for communities is to not just sweep people away like trash, but to show up for those who are unhoused with grace and compassion through outreach, advocacy and volunteering.

_____

Amy Shea is the writing program director at Mount Tamalpais College — a free community college for the incarcerated people of San Quentin State Rehabilitation Center. She is the author of the new book, “Too Poor to Die: The Hidden Realities of Dying in the Margins” (Rutgers University Press). This column was produced for Progressive Perspectives, a project of The Progressive magazine, and distributed by Tribune News Service.

_____

©2025 Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments